We had a message come to us that said if you are looking for wild stories from small towns you need to read into the past of Burke Idaho. Naturally, I was thinking alright well what happened with a state full of potatoes? Ironically the day I was doing research on this it was national potato day. So happy belated national potato day everyone. So we are going to talk about a town that is filled with violence and unfortunate tragedy. Buckle up because we are about to go on a wild adventure through the past courtesy of Burke Idaho.

Burke Idaho according to Wikipedia is a ghost town in Shoshone County, Idaho, United States, established in 1887. Once a thriving silver, lead, and zinc mining community, the town saw a significant decline in the mid-twentieth century after the closure of several mines. It’s in Shoshone County that went from 1400 people in the early 1900s to around 15 people in the 1990s. Why did 15 people choose to live here and why are only 15 people living there? Well, let’s jump right into it.

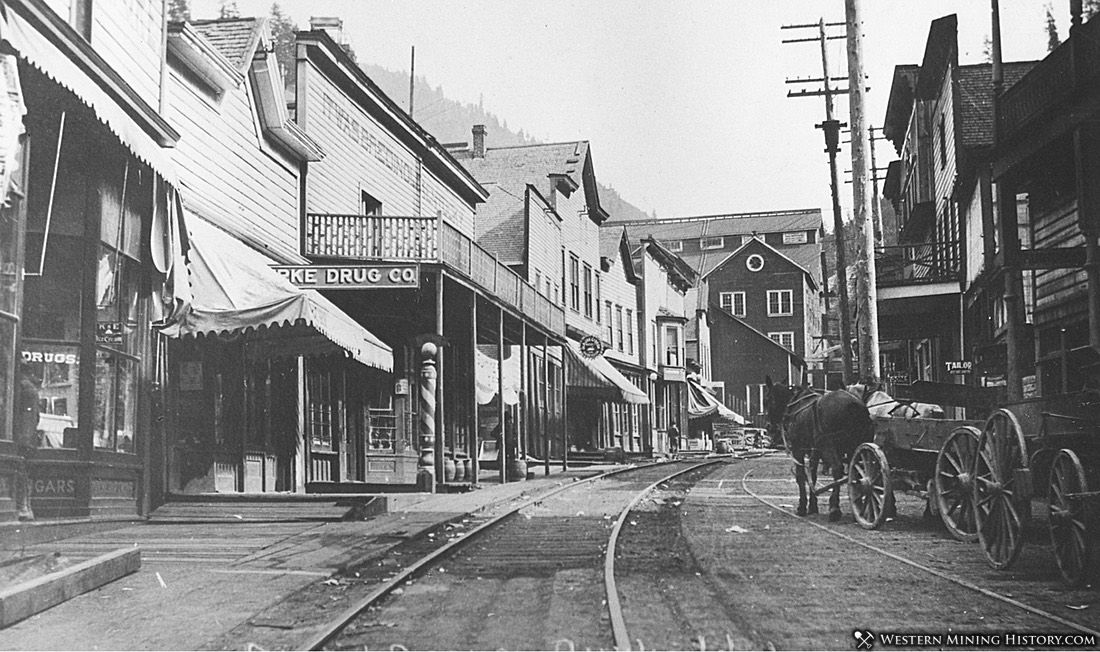

The mining town was formed after the discovery of rich deposits of silver and lead were discovered in 1884 in Burke Canyon. Burke Canyon is long and thing only 300 feet wide at its narrowest point. Many would think it would be impossible to fit a whole town into that kind of space. But they figured it out.

The first mine in Burke, the Tiger Mine, was discovered in May 1884.[8] That same year, the Tiger Mine was sold to S.S. Glidden for $35,000.By the end of 1885, over 3,000 tons of ore had been extracted from the Tiger Mine.[10] The high volume of ore being extracted from the mountains led Glidden to begin construction on a railroad from the mine to Wallace. On July 6, 1887, Glidden incorporated the Canyon Creek Railroad, a 3 ft wide narrow-gauge railway that operated from Wallace to the Tiger Mine.[9] Additional investors on the Canyon Creek Railroad were Harry M. Glidden, Frank R. Culbertson, Alexander H. Tarbet, and Charles W. O'Neil.[9]

By September 1887, little work had been accomplished on the railway; accumulations of mined ore in the area had reached over 100,000 pounds, pressuring Glidden to sell the line to D.C. Corbin.[11] Under Corbin's overseeing, by November 1887, 3 miles (4.8 km) of tracks had been laid, and it was then that the town of Burke was formally established. The town was so small as mentioned that vehicles had to share the road with the trains and when trains came through vehicles and people had to move out of the way. In 1886 the Tiger Hotel was built to be able to house miners. This three-story hotel straddled the main street and the railroad had to run through the lobby of this 150-room Tiger Hotel because there just wasn’t enough room. Not only did it have a train track running through it, it had two sets of tracks and a stream running through it’s lobby. Talk about a rough night of sleep when the train runs through the lobby huh? Things were going pretty decent in Burke for the first couple of years. Business is booming trains are rolling streams are streaming.

February 4, 1890, the first of several avalanches in Burke's history caused major damage to the residences and businesses in the town, and killed three people.

It was then in 1891 tensions started to mount between miners and the mining companies. At this time it seemed bad but in 1892 it got really really bad. In 1892 hard rock miners started to strike as their wages were cut. The miners demanded that a "living wage" of $3.50 per day[5] be paid to every man working underground and the common laborer as well as the skilled. Other mines started to pop up in the area and a lot of the workers would go there to work during the strike. The strike was called the Coeur d'Alene labor strike and it erupted in violence. You had 3000 higher paid miners standing up for 500 lower-paid laborers and this was rare. The labor union miners discovered they had been infiltrated by a Pinkerton agent who had routinely provided union information to the mine owners. The Pinkertons and other agents went into the district in large numbers. Soon there was a significant security force available to protect new workers coming into the mines. For a time the struggle manifested as a war of words in the local newspapers, with mine owners and mine workers denouncing each other.

An undercover Pinkerton agent, soon-to-be well-known lawman Charlie Siringo, had worked in the Gem Mine as a shoveler. Using the alias Charles Leon Allison, Siringo joined the Gem Miners' Union, and was elected recording secretary, providing him with access to all of the union's books and records. Siringo found the "leaders of the Coeur d'Alene unions to be, as a rule, a vicious, heartless gang of anarchists.

On Sunday night, July 10, armed union miners gathered on the hills above the Frisco mine. More union miners were arriving from surrounding communities. Strikers opened fire at 5 am on July 11, 1892, and guards and workers in the mill building returned fire.[14] The guards and strikebreakers inside the mine and mill buildings were prepared for a long standoff, having been warned by Charlie Siringo. Both sides began shooting to kill. After three and a half hours of gunfire without casualties, striking miners on the hill above sent a bundle of dynamite down a sluice into the mill, destroying the building and crushing one of the strikebreakers. The rest of the strikebreakers in the wrecked Frisco mill surrendered and were taken to the union hall as prisoners.

After the Helena-Frisco strikebreakers surrendered, the striking miners shifted to the Gem mine, where a similar gunfight took place. The Gem miners were well-entrenched, but the Gem management, fearing similar destruction of property as took place at the Frisco, ordered the men to surrender. Three Union men, one company guard, and one strikebreaker were killed by gunfire before the strikebreakers surrendered. At the end of the day, six men were dead, three on each side, and there were 150 strikebreakers and guards held prisoner in the union hall. They were put on a train and were told to leave the county.

It was so out of hand the governor declared Martial law and ordered the Idaho National Guard to come to assist. They ruled the town for four straight months to get the order back in place.

The dust settles and Burke continued the development of the Tiger Hotel, A grease fire severely damaged the hotel shortly after killing three people in 1896.

Then in 1899 violence in the mines erupts again in response to the Bunker Hill company firing seventeen men for joining the union, the miners dynamited the Bunker Hill & Sullivan mill. Lives were lost once again, and the army intervened. It was reported that 100 men went to Frisco Mines and loaded 80 crates containing 50 pounds of dynamite. More and more miners came carrying more and more dynamite until eventually after all of the gunfire and explosions the mine was completely destroyed. The army then came back in to restore control of this town.

The city and surrounding mines continued to prosper reaching its peak in population in 1910 at around 1400 people. You will never guess this but tragedy strikes again in February of 1910 when an avalanche strikes the town killing 20.

Six months later the Great Fire of 1910 occurs causing more damage to the town.

If that wasn’t enough in 1913 there was a flood that impacted the town with sediment and debris building up against the Tiger Hotel as water cascaded down the gulch. The town was impacted by further damage on July 23, 1923, when another fire broke out, causing extensive damage to numerous buildings in the town. The fire was caused by the spark of a train going through town and impacted 50 houses and businesses. The damage was estimated to be a million dollars and left 600 people homeless. The Helca mine was shut down for several months to be rebuilt. The Most notably damaged by the fire was the Tiger Hotel, which became increasingly unprofitable in the 1940s and was torn down in 1954.

By the mid-twentieth century, mining operations in Burke had slowed after the closure of several mines. The last mine in Burke closed in 1991. According to U.S. census data, there were a total of fifteen residents in Burke in 1990.

Between avalanches, floods, and fires, Burke saw more than its share of natural disasters over the years. Today, only a handful of residents remain in the canyon between Wallace and Burke. Of Mace itself, only rubble marks the foundation of a town fading from memory.

Sources

https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/idaho/burke/

Wikipedia

https://www.historynet.com/disaster-burke-canyon/

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/burke-ghost-town

https://writergirlm.com/2020/03/echoes-of-the-past-in-burke-idaho/

https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/idaho/abandoned-mining-town-burke-id/